Also in:

![]() 简中 (简中)

简中 (简中)

過去這個週末學生考了 2017 年 8 月的 SAT 考試。如果這是你最後一次考 SAT,恭喜你完成了一個艱難的任務!

這裡,我們整理了 2017 年 8 月 SAT 考試當中的 5 篇閱讀文章,幫助學生準備未來的考試。

這些閱讀文章可以如何的幫助你?

1. 這些文章可以讓你知道你的英文程度以及準備考試的程度

首先,讀這些文章。你覺得他們讀起來很簡單還是很難?裡面有沒有很多生字,尤其是那些會影響你理解整篇文章的生字?如果有的話,雖然你可能是在美國讀書或讀國際學校、也知道 “如何讀跟寫英文”,但你還沒有足夠的生字基礎讓你 “達到下一個階段” (也就是大學的階段)。查一下這一些字,然後把它們背起來。這些生字不見得會在下一個 SAT 考試中出現,但是透過真正的 SAT 閱讀文章去認識及學習這些生字可以大大的減低考試中出現不會的生字的機率。

2. 這些文章會告訴你平時應該要讀哪些文章幫你準備閱讀考試

在我們的 Ivy-Way Reading Workbook(Ivy-Way 閱讀技巧書)的第一章節裡,我們教學生在閱讀文章之前要先讀文章最上面的開頭介紹。雖然你的 SAT 考試不會剛好考這幾篇文章,但你還是可以透過這些文章找到它們的來源,然後從來源閱讀更多相關的文章。舉例來說,如果你看第二篇文章 “The Problem with Fair Trade Coffee”,你會看到文章是來自 Stanford Social Innovation Review。閱讀更多來自 Stanford Social Innovation Review 的文章會幫助你習慣閱讀這種風格的文章。

3. 這些文章會幫助你發掘閱讀單元的技巧(如果閱讀單元對你來說不是特別簡單的話)

如果你覺得閱讀單元很簡單,或是你在做完之後還有剩幾分鐘可以檢查,那麼這個技巧可能就對你來說沒有特別大的幫助。但是,如果你覺得閱讀很難,或者你常常不夠時間做題,一個很好的技巧是先理解那一種的文章對你來說比較難,然後最後做這一篇文章。SAT 的閱讀文章包含這五種類型:

- 文學 (literature):1 篇經典或現代的文學文章(通常來自美國)

- 歷史 (History):1 篇跟美國獨立/創立相關的文章,或者一篇受到美國獨立 / 創立影響的國際文章(像是美國憲法或者馬丁路德金恩 (Martin Luther King Jr.) 的演說)

- 人文 (Humanities):1 篇經濟、心理學、社會學、或社會科學的文章

- 科學 (Sciences):1-2 篇地理、生物、化學、或物理的文章

- 雙篇文 (Dual-Passages):0-1 篇含有兩篇同主題的文章

舉例來說,假設你覺得跟美國獨立相關的文章是你在做連續的時候覺得最難的種類,那你在考試的時候可以考慮使用的技巧之一是把這篇文章留到最後再做。這樣一來,如果你在考試到最後時間不夠了,你還是可以從其他比較簡單文章中盡量拿分。

所有 2017 年 8 月 (北美) SAT 考試閱讀文章

PASSAGE 1

This passage is from Paul Laurence Dunber, The Sport of the Gods. Originally published in 1901.

Then the work began. The man was indefatigable. He was like the spirit of energy. He was in every place about the stage at once, leading the chorus, showing them steps, twisting some awkward girl into shape, shouting, gesticulating, abusing the pianist.

“Now, now,” he would shout. “the left foot on that beat. Bah, bah, stop! You walk like a lot of tin soldiers. Are your joints rusty? Do you want oil? Look here, Taylor, if 1 didn’t know you, I’d take you for a truck. Pick up your feet, open your mouths, and move, move, move! Oh!” and he would drop his head in despair. “And to think that I’ve got to do something with these things in two weeks—two weeks!” Then he would turn to them again with a sudden reaccession of eagerness. “Now, at it again, at it again! Hold that note, hold it! Now whirl, and on the left foot. Stop that music, stop it! Miss Coster, you’ll learn that step in about a thousand years, and I’ve got nine hundred and ninety-nine years and fifty weeks less time than that to spare. Come here and try that step with me. Don’t be afraid to move. Step like a chicken on a hot griddle!” And some blushing girl would come forward and go through the step alone before all the rest.

Kitty contemplated the scene with a mind equally divided between fear and anger. What should she do if he should so speak to her? Like the others, no doubt, smile sheepishly and obey him. But she did not like to believe it. She felt that the independence which she had known from babyhood would assert itself, and that she would talk back to him, even as Hattie Sterling did. She felt scared and discouraged, but every now and then her friend smiled encouragingly upon her across the ranks of moving singers.

Finally. however, her thoughts were broken in uponby hearing Mr. Martin cry: “Oh, quit, quit, and go rest yourselves, you ancient pieces of hickory, and let me forget you for a minute before I go crazy. Where’s that new girl now?”

Kitty rose and went toward him, trembling so that she could hardly walk.

“What can you do?”

“I can sing,” very faintly.

“Well, if that ‘s the voice you ‘re going to sing in, there won’t be many that’ll know whether it’s good or bad. Well, let ‘s hear something. Do you know any of these?”

And he ran over the titles of several songs. She knew some of them, and he selected one. “Try this. Here, Tom, play it for her.”

It was an ordeal for the girl to go through. She had never sung before at anything more formidable than a church concert, where only her immediate acquaintances and townspeople were present. Now to sing before all these strange people, themselves singers, made her feel faint and awkward. But the courage of desperation came to her, and she struck into the song. At the first her voice wavered and threatened to fail her. It must not. She choked back her fright and forced the music from her lips.

When she was done, she was startled to hear Martin burst into a raucous laugh. Such humiliation! She had failed, and instead of telling her, he was bringing her to shame before the whole company. The tears came into her eyes, and she was about giving way when she caught a reassuring nod and smile from Hattie Sterling, and seized on this as a last hope. “Haw, haw, haw!” laughed Martin,

“haw, haw, haw! The little one was scared, see? She was scared, d’ you understand? But did you see the grit she went at it with? Just took the bit in her teeth and got away. Haw, haw, haw! Now, that ‘s what I like. If all you girls had that spirit, we could do something in two weeks. Try another one, girl.”

Kitty’s heart had suddenly grown light. She sang the second one better because something within her was singing.

PASSAGE 2

Passages 1, by James Kent, and passage 2, by David Buel, are adapted from speeches delivered to the New York Constitutional Convention in 1821. Both address the requirement in the New York State Constitution that only property-owning rules should be granted suffrage the right to vote.

Passage 1

The tendency of universal suffrage, is to jeopardize the rights of property and principles of liberty…Who can undertake to calculator with any precision, how many millions of people, this great state will contain in the course of this and the next century, and who can estimate the future extent and magnitude of our commercial ports? The disproportion between the men of property, and the men of no property, will be in every society in a ratio to its commerce, wealth, and population. We arc no longer to remain plain and simple republics of farmers, like the New England colonists, or the Dutch settlements in the Hudson. We arc fast becoming a great nation, with great commerce. manufactures, population, wealth, luxuries, and with the vises and miseries that they engender. One seventh of the population of city of Paris at this day subsists on charity, and one third of the inhabitants of that city die in hospitals; what would become of such a city with universal suffrage?

…The notion that every man that works a day on the road, or serves an idle hour in the militia, is entitled as of right to an equal participation in the whole power of the government, is most unreasonable, and has no foundation in justice…

Liberty, rightly understood, is an inestimable blessing, but liberty without wisdom, and without justice, is no better than wild and savage licentiousness. The danger which we have hereafter to apprehend, is not the want, but the abuse, of liberty…A stable senate, exempted from the influence of universal suffrage, will powerfully check these dangerous propensities, and such a check becomes the more necessary, since the Convention has already determined to withdraw the watchful eye of the judicial department from the passage of laws.

Passage 2

The farmers in this country will always out number all other portions of our population. Admitting that the increase of our cities, and especially of our commercial metropolis, will be as great as it has been hitherto; it is not to be doubted that the agricultural population will increase in the same proportion. The city population will never be able to depress that of the country. New York has always contained about a tenth part of the population of the state, and will probably always bear a similar proportion. Can she, with such a population, under any circumstances, render the property of the vast population of the country insecure? It may be that mobs will occasionally be collected, and commit depredations in a great city, but, can the mobs traverse our immense territory, and invade the farms, and despoil the property of the landholders? And if such a state of things were possible, would a senate, elected by freeholders, afford any security?

…I contend that by the true principle of our government, property, as such, is not the basis of representation. Our community is an association of persons-of human beings-not a partnership founded on property. The declared object of the people of this state in associating, was, to “establish such a government as they deemed best calculated to secure the rights and liberties of the good people of the state, and most conducive to their happiness and safety.”Property, it is admitted, is one of the rights to be protected and secured; and although the protection of life and liberty is the highest object of attention, it is certainly true, that the security of property is a most interesting and important object in every free government. Property is essential to our temporal happiness; and is necessarily one of the most interesting subjects of legislation. The desire of acquiring property is a universal passion…To property we are indebted for most of our comforts, and for much of our temporal happiness. The numerous religious, moral, and benevolent institutions which are every where established, owe their existence to wealth; and it is wealth which enables us to make those great internal improvement which we have undertaken. Property is only one of the incidental rights of the person who possesses it; and, as such, it must be made secure, but it does not follow, that it must therefore be represented specifically in any branch of the government.

Passage 3

This passage is a adapted from P.H, “Memory in Plants.” 2014 by The Economist Newspaper Limited.

When Britain’s Prince Charles once claimed that he talked to his plants—and that they responded—critics chalked it up as one more reason why he should never become king. With tongue more firmly in cheek, the prince says that these days he merely “instructs” his leafy subjects. But do they listen to, learn from, or remember his royal commands?

More than a century ago Bengali polymath Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose posited that plants could feel, learn and remember, and more recent studies have confirmed they can store and recall biological data. But research by Monica Gagliano of the University of Western Australia (UWA) and three fellow scientists goes much further. This study, published in Oecologia ,offers proof that plants not only learn from experience, but remember what they have learned over relatively long periods.

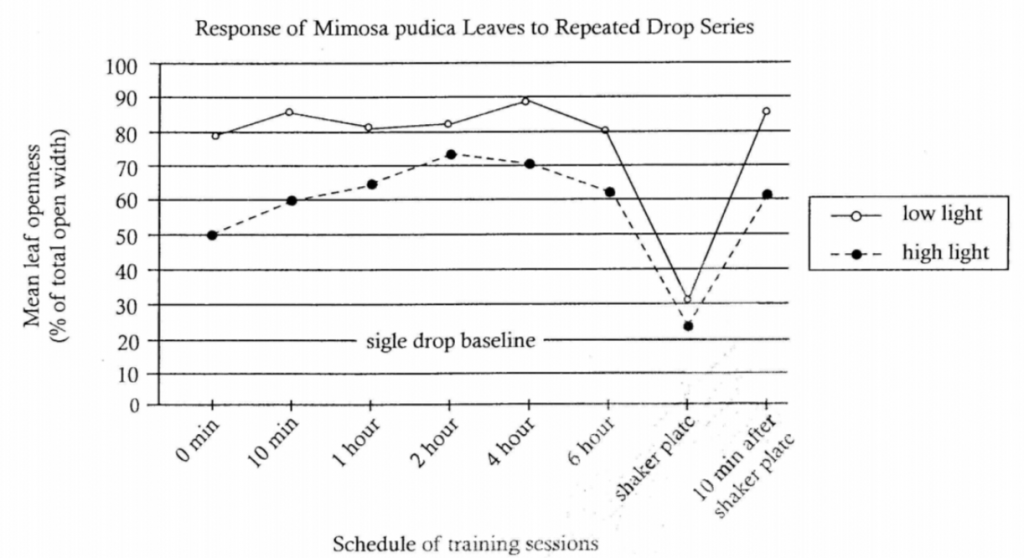

Dr. Gagliano and collaborators Michael Renton, Martial Depczynski ( all from UWA ) and Stefano Mancuso (of Florence University ) chose as their subject the herb Mimosa pudica, often known as the touch-me-not because its leaves fold swiftly inwards when disturbed—a mechanism designed to defend it against predators.

The team devised an apparatus that suspend each potted mimosa on a vertical rail above a foam base, then dropped it 15cm by allowing it to slide down the rail—a significant physical shocks, but ultimately not a threat to the plant’s well-being. Their goal was to discover if mimosas could adaptively learn to ignore such stimuli, a process known as habituation. The plants were variously grown in low-light (LL) and high-light (HL) environments, with the expectation that the LL plants would “learn” more quickly given their greater need to keep their leaveS open for photosynthesis.

Mimosas subjected to a single drop quickly closed their leaves, and did so again when the experiment was repeated eight hours later —clearly they still considered the experience threatening. A large group of plants was then trained with a series of 60 consecutive drops a few seconds apart, repeated seven times within a single day. These plants habituated rapidly, keeping their leaves open after the first four to six initial drops and ,towards the end of the day’s training, not closing their leaves at all (as expected, the LL plants leaves re-opened more widely). To ensure that all this was not simply a case of “fall-fatigue,” a different kind of shock (on a 250-rpm “shaker plate”) was administered after the sixth training. The mimosas closed their leaves.

What is most remarkable, however, is that the plants remembered their training. Some mimosas that were subjected to single series of 60 drops six days later did not close their leaves at all, while those that did react stopped doing so after only two or three drops. A number of plants were then switched from LL to HL (and vice versa), left undisturbed for 28 days. and “re-tested” by being given the full day’s training again. Intriguingly, the HL-to-LL plants not only remembered that the stimulus was harmless, but also opened their leaves more widely, showing that they had adapted what they had learned to their new LL environment. Overall, both groups displayed more pronounced and consistent responses than before, demonstrating that they still recall what they were taught four weeks earlier.

Dr. Gagliano and her colleagues admit that they do not conclusively know how plants—lacking brains or neutral tissue—learn and remember. Calcium-based cellular signalling is one possible explanation, as is the processing of information by cells via ion flows—plants have well-established pathways to transmit information via electrical signals.

All of which suggests that Prince Charles may yet be vindicted.

Passage 4

This passage is adapted from Detlef Fetchenhauer and David Dunning, ‘Why So Cynical? Asymmetric Feedback Underlies Misguided Skepticism Regarding the Trustworthiness of Others.”02010 by Detlef Fetchenhauer and David Dunning.

People can be cynical to a fault. They underestimate how often others respond generously to request for help and overestimate how much others’ attitudes and actions are driven by selfish concerns. To be sure, there is contrary evidence showing that people can be roughly realistic in anticipating the altruism of others, but an increasing body of evidence suggests that when people are contemplating whether they should rely on the kindness of strangers, they suspect those strangers will prove more selfish than actually is the case.

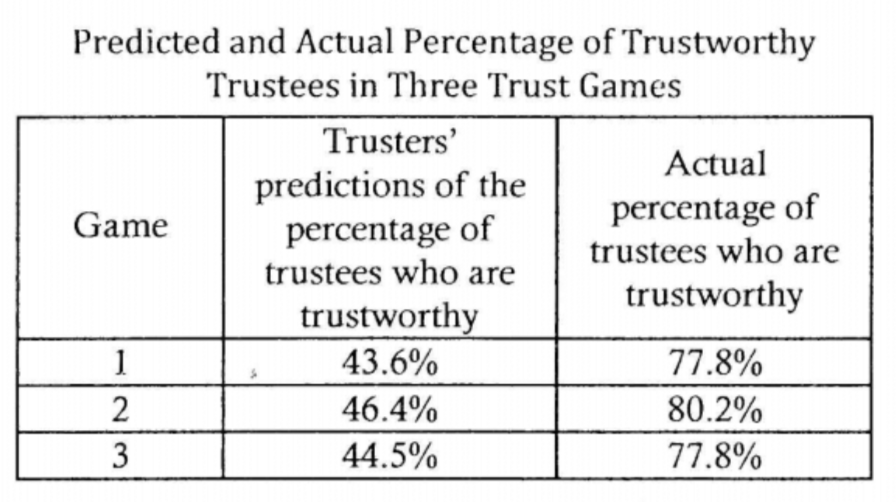

We have previously shown this cynicism most clearly in experiments using the economic paradigm known as the ” trust ” or “investment” game. In the game, the truster is given money that can be kept or handed to a completely random and anonymous stranger, the trustee. If the truster hands his or her money over. The amount of money is quadrupled (e.g., $5 becomes $20), and trustees have two options: They can either split the money evenly between themselves and the truster (e.g., give $10 back and keep $10 for themselves), or they can keep all the money for themselves.

In a number of studies, we have shown that the vast majority of trustees honor the trust that is offered them, giving money back even when their identities are anonymous and they are under no compulsion to act generously. However, most truster severely underestimate their fellow participants’ trustworthiness. Although 80% to 90% of trustees honor trust, trusters on average estimate that this rate will be only 45% to 60%.

Such cynicism may matter, in that it leads people to refrain from trusting, and thus pass up likely monetary gains. For example, in versions of the game in which people can decide the exact amount of money to transfer to the trustee, many people pass along only a little money. This causes trustees to pass back little although they would have been quite generous if they had been trusted more completely. Similarly, when trusters impose possible penalties if trustees are not generous enough in return, trustees respond by passing back significantly less than they would otherwise.

The research reported here investigated how such skepticism toward others can be explained. We focused on two possible determinants. First, participants may not be sufficiently motivated to provide accurate estimates of trustworthiness. Behavioral economists would argue that participants provide valid estimates only if they have a sufficient material incentive to do so, although this argument cannot explain why estimates arc so biased in one direction.

Second. when people decide whether to trust, they can make two mistakes. They can trust someone whose intentions are actually harmful, or they can refuse o trust a person who would actually reciprocate that trust. The chance that life informs them about these two mistakes is asymmetric. When people trust another person and that person betrays their trust, people become painfully aware of that betrayal. However, if people distrust another person. they never give that person a chance to act in a trustworthy way. Thus, people preclude themselves from learning when others, despite expectations, might prove trustworthy.

In essence, we argue for an experience -sampling explanation for unwarranted cynicism in situations involving trust. When people trust and that trust is exploited, they become more cynical. However, when they mistakenly fail to trust a trustworthy person, they avoid the experience that would provide feedback to correct that mistake. Thus, their overall impression of human nature is left overly cynical.

Passage 5

This passage is adapted from Susan W. Kieffer, “The Deadly Dynamics of Landsliders,” ©2014 by Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society.

Approximately 17,000 years ago, a volume of rock equal to a cube about a half-mile on a side roared out of a steep canyon in the San Bernardino Mountains in southern California. It originated 1,500 feet above the canyon bottom. Rocks in the slide, already fractured at the start of the event, shattered on impact with the canyon bottom, forming intricate three-dimensional jigsaw puzzles. When this event, known as the Blackhawk slide, excited from the canyon, it ran out across a nearly flat valley floor for five miles. Amazingly, the pieces of the jigsaw puzzles stayed together as the slide zoomed along at nearly 75 miles an hour. A similar landslide triggered by the 1964 Alaska earthquake traveled three miles across the nearly level Sherman Glacier before coming to rest. Where the base of the landslide could be seen on the glacier, it rested on—believe it or not–undisturbed snow. In other places it left alders, mosses, and small plants completely undisturbed.

The observations from the Alaska, and geological evidence from the Blackhawk landslide, led to the intriguing hypothesis that landslide can be transported like flexible sheets over a cushion of trapped and compressed air—literally like a flying carpet. Imagine such huge masses of rock roaring down a canyon, hitting a resistant ledge, being launched hundreds of feet into the air, setting back onto a blanket of compressed air only a few feet thick, and then hurling out at breakneck speeds onto the desert floor until the air leaks out and the slide gently glides to a halt, the whole event taking perhaps a minute or two. In this “air lubrication” hypothesis, the landslide floats as a nearly rigid stab on its cushion of air, so fragile jigsaw pieces of rock such as those observed at Blackhawk are preserved.

Although the air lubrication hypothesis may work for specific slides, two arguments suggest that it cannot explain all long runouts. First is the question of whether the air can stay trapped under the slide long enough for the runout, because it would tend to diffuse through the slide and around its edges. The second problem, which became obvious as a result of unmanned spacecraft looking at the planets and their satellites in the Solar System, is that long runout landslides occur on our Moon and on four other moons in our Solar System that have no atmosphere—Io, Callisto, Phobos, and Iapetus. Such slides also occur on Mars, which currently has only a very thin atmosphere, although it is not known what the atmosphere was like when the landslides formed in the past. Long runout slides on airless or nearly airless bodies have forced geologists to look at explanation other than air lubrication.

One group of theories takes into account the fact that landslides are not monolithic slabs of rock, but consist of rock fragments of many different sizes. They fall into the broad category of materials called “granular matter” that have unique properties. The cereal in your breakfast bowl provides an example. Sometimes these materials behave very much like a solid, and other times they flow like a liquid. Grains can flow, slosh, and reflect from boundaries like a liquid, they can erode channels just like flowing water, and in some instances they can produce hills and gullies that mimic features formed by flowing water.

Increasingly, evidence has been mounting that lubrication is enhanced also by liquid water, ice, wet debris, or mud at the base of the slide, or perhaps water within the slide. Even if landslides are not saturated with water, they are unlikely to be completely dry; they will always contain some liquid water (on Earth) or ice (on Earth and the other planets or satellites). Water is effective at lubricating debris and mudflows. Sometimes water on the surface of the Earth provides a layer over which a landslide hydroplanes like a boat.

Even these possibilities do not exhaust the ideas proposed for long-runout slides. By studying landslides at these many scales, geoscientists have come up with such a bewildering array of proposals for how they move that it may sound as if we simply don’t know what we are talking about. In truth, some of the processes proposed almost certainly occur some of the time in some of the landslides, and not all of the processes occur all of the time or in all places. The large number of hypotheses and mechanisms proposed is testimony to the awesome complexity of our world.

2017年 8月 (北美) SAT 考試閱讀題目

Ivy-Way 學生在上課的過程就會做到2017年8月以及其他的官方歷年考題。除此之外,我們也有讓學生來我們的教室或在家做模考的服務讓學生評估自己的學習進度並看到成績。如果你想預約時間來我們的教室或在家做模考,請聯繫我們!

Also in:

![]() 简中 (简中)

简中 (简中)