Also in:

![]() 简中 (简中)

简中 (简中)

過去這個週末學生考了 2017 年 10 月的 SAT 考試。如果這是你最後一次考 SAT,恭喜你完成了一個艱難的任務!

這裡,我們整理了 2017 年 10 月 SAT 考試當中的 5 篇閱讀文章,幫助學生準備未來的考試。

這些閱讀文章可以如何的幫助你?

1. 這些文章可以讓你知道你的英文程度以及準備考試的程度

首先,讀這些文章。你覺得他們讀起來很簡單還是很難?裡面有沒有很多生字,尤其是那些會影響你理解整篇文章的生字?如果有的話,雖然你可能是在美國讀書或讀國際學校、也知道 “如何讀跟寫英文”,但你還沒有足夠的生字基礎讓你 “達到下一個階段” (也就是大學的階段)。查一下這一些字,然後把它們背起來。這些生字不見得會在下一個 SAT 考試中出現,但是透過真正的 SAT 閱讀文章去認識及學習這些生字可以大大的減低考試中出現不會的生字的機率。

2. 這些文章會告訴你平時應該要讀哪些文章幫你準備閱讀考試

在我們的 Ivy-Way Reading Workbook(Ivy-Way 閱讀技巧書)的第一章節裡,我們教學生在閱讀文章之前要先讀文章最上面的開頭介紹。雖然你的 SAT 考試不會剛好考這幾篇文章,但你還是可以透過這些文章找到它們的來源,然後從來源閱讀更多相關的文章。舉例來說,如果你看第二篇文章 “The Problem with Fair Trade Coffee”,你會看到文章是來自 Stanford Social Innovation Review。閱讀更多來自 Stanford Social Innovation Review 的文章會幫助你習慣閱讀這種風格的文章。

3. 這些文章會幫助你發掘閱讀單元的技巧(如果閱讀單元對你來說不是特別簡單的話)

如果你覺得閱讀單元很簡單,或是你在做完之後還有剩幾分鐘可以檢查,那麼這個技巧可能就對你來說沒有特別大的幫助。但是,如果你覺得閱讀很難,或者你常常不夠時間做題,一個很好的技巧是先理解那一種的文章對你來說比較難,然後最後做這一篇文章。SAT 的閱讀文章包含這五種類型:

- 文學 (literature):1 篇經典或現代的文學文章(通常來自美國)

- 歷史 (History):1 篇跟美國獨立/創立相關的文章,或者一篇受到美國獨立 / 創立影響的國際文章(像是美國憲法或者馬丁路德金恩 (Martin Luther King Jr.) 的演說)

- 人文 (Humanities):1 篇經濟、心理學、社會學、或社會科學的文章

- 科學 (Sciences):1-2 篇地理、生物、化學、或物理的文章

- 雙篇文 (Dual-Passages):0-1 篇含有兩篇同主題的文章

舉例來說,假設你覺得跟美國獨立相關的文章是你在做連續的時候覺得最難的種類,那你在考試的時候可以考慮使用的技巧之一是把這篇文章留到最後再做。這樣一來,如果你在考試到最後時間不夠了,你還是可以從其他比較簡單文章中盡量拿分。

所有 2017 年 10 月 (北美) SAT 考試閱讀文章

PASSAGE 1

This passage is adapted from Amy Tan, The Bonesetter’s Daughter. ©2001 by Amy Tan.

At last, Old Widow Lau was done haggling with the driver and we stepped inside Father’s shop. It was north-facing, quite dim inside, and perhaps this was why Father did not see us at first. He was busy with a customer, a man who was distinguished-looking, like the scholars of two decades before. The two men were bent over a glass case, discussing the different qualities of inksticks. Big Uncle welcomed us and invited us to be seated. From his formal tone, I knew he did not recognize who we were. So I called his name in a shy voice. And he squinted at me, then laughed and announced our arrival to Little Uncle, who apologized many times for not rushing over sooner to greet us. They rushed us to be seated at one of two tea tables for customers. Old Widow Lau refused their invitation three times, exclaiming that my father and uncles must be too busy for visitors. She made weak efforts to leave. On the fourth insistence, we finally sat. Then Little Uncle brought us hot tea and sweet oranges, as well as bamboo latticework fans with which to cool ourselves.

I tried to notice everything so I could later tell GaoLing what I had seen, and tease out her envy. The floors of the shop were of dark wood, polished and clean, no dirty footprints, even though this was during the dustiest part of the summer. And along the walls were display cases made of wood and glass.

The glass was very shiny and not one pane was broken. Within those glass cases were our silk-wrapped boxes, all our hard work. They looked so much nicer than they had in the ink-making studio at Immortal Heart village.

I saw that Father had opened several of the boxes. He set sticks and cakes and other shapes on a silk cloth covering a glass case that served as a table on which he and the customer leaned. First he pointed to a stick with a top shaped like a fairy boat and said with graceful importance, “Your writing will flow as smoothly as a keel cutting through a glassy lake.” He picked up a bird shape: “Your mind will soar into the clouds of higher thought.” He waved toward a row of ink cakes embellished with designs of peonies and bamboo: “Your ledgers will blossom into abundance while bamboo surrounds your quiet mind.”

As he said this, Precious Auntie came back into mind. I was remembering how she taught me that everything, even ink, had a purpose and a meaning: Good ink cannot be the quick kind, ready to pour out of a bottle. You can never be an artist if your work comes without effort. That is the problem of modern ink from a bottle. You do not have to think. You simply write what is swimming on the top of your brain. And the top is nothing but pond scum, dead leaves, and mosquito spawn. But when you push an inkstick along an inkstone, you take the first step to cleansing your mind and your heart. You push and you ask yourself, What are my intentions? What is in my heart that matches my mind?

I remembered this, and yet that day in the ink shop, I listened to what Father was saying, and his words became far more important than anything Precious Auntie had thought. “Look here,” Father said to his customer, and I looked. He held up an inkstick and rotated it in the light. “See? It’s the right hue, purple-black, not brown or gray like the cheap brands you might find down the street. And listen to this.” And I heard a sound as clean and pure as a small silver bell. “The high-pitched tone tells you that the soot is very fine, as smooth as the sliding banks of old rivers. And the scent—can you smell the balance of strength and delicacy, the musical notes of the ink’s perfume? Expensive, and everyone who sees you using it will know that it was well worth the high price.”

I was very proud to hear Father speak of our family’s ink this way.

PASSAGE 2

This passage is adapted from “How the Web Affects Memory.” ©2011 by Harvard Magazine Inc.

Search engines have changed the way we use the Internet, putting vast sources of information just a few clicks away. But Harvard professor of psychology Daniel Wegner’s recent research proves that websites—and the Internet—are changing much more than technology itself. They are changing the way our memories function.

Wegner’s latest study, “Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips,” shows that when people have access to search engines, they remember fewer facts and less information because they know they can rely on “search” as a readily available shortcut.

Wegner, the senior author of the study, believes the new findings show that the Internet has become part of a transactive memory source, a method by which our brains compartmentalize information. First hypothesized by Wegner in 1985, transactive memory exists in many forms, as when a husband relies on his wife to remember a relative’s birthday. “[It is] this whole network of memory where you don’t have to remember everything in the world yourself,” he says. “You just have to remember who knows it.” Now computers and technology as well are becoming virtual extensions of our memory.

The idea validates habits already forming in our daily lives. Cell phones have become the primary location for phone numbers. GPS devices in cars remove the need to memorize directions. Wegner points out that we never have to stretch our memories too far to remember the name of an obscure movie actor or the capital of Kyrgyzstan—we just type our questions into Google. “We become part of the Internet in a way,” he says. “We become part of the system and we end up trusting it.”

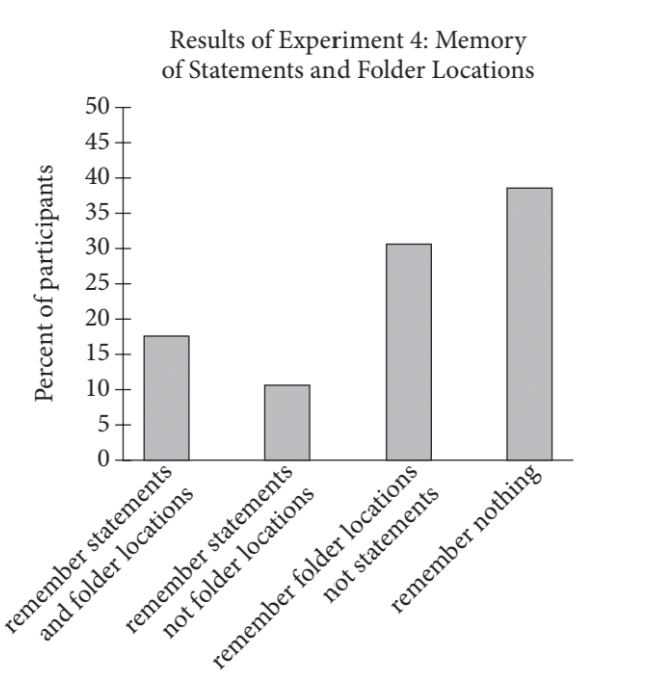

Working with researchers Betsy Sparrow of Columbia University and Jenny Liu of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wegner conducted four experiments to demonstrate the phenomenon, using various forms of memory recall to test reliance on computers. In the first experiment, participants demonstrated that they were more likely to think of computer terms like “Yahoo” or “Google” after being asked a set of difficult trivia questions. In two other experiments, participants were asked to type a collection of readily memorable statements, such as “An ostrich’s eye is bigger than its brain.” Half the subjects were told that their work would be saved to a computer; the other half were informed that the statements would be erased. In subsequent memory testing, participants who were told their work would not be saved were best at recalling the statements. In a fourth experiment, participants typed into a computer statements they were told would be saved in specific folders. Next, they were asked to recall the statements. Finally, they were given cues to the wording and asked to name the folders where the statements were stored. The participants proved better able to recall the folder locations than the statements themselves.

Wegner concedes that questions remain about whether dependence on computers will affect memories negatively: “Nobody knows now what the effects are of these tools on logical thinking.” Students who have trouble remembering distinct facts, for example, may struggle to employ those facts in critical thinking. But he believes that the situation overall is beneficial, likening dependence on computers to dependence on a mechanical hand or other prosthetic device.

And even though we may not be taxing our memories to recall distinct facts, we are still using them to consider where the facts are located and how to access them. “We still have to remember things,” Wegner explains. “We’re just remembering a different range of things.” He believes his study will lead to further research into understanding computer dependence, and looks forward to tracing the extent of human interdependence with the computer world—pinpointing the “movable dividing line between us and our computers in cyber networks.”

Passage 3

This passage is adapted from Marlene Zuk, Paleofantasy: What Evolution Really Tells Us about Sex, Diet, and How We Live. ©2013 by Marlene Zuk.

A female guppy can be sexually mature at two months of age and have her first babies just a month later. This unstinting rate of reproduction makes guppies ideally suited for studying the rate of evolution, and David Reznick, a biologist at UC Riverside, has been doing exactly that for the last few decades.

People usually think of guppies as colorful aquarium fish, but they also have a life in the real world, inhabiting streams and rivers in tropical places like Trinidad, where Reznick has done his fieldwork. Guppies can experience different kinds of conditions depending on the luck of the draw. A lucky guppy is born above a waterfall or a set of rapids, which keep out the predatory fish called pike cichlids found in calmer downstream waters. As you might expect, the guppy mortality rate—that is, the proportion of individuals that die—is much higher in the sites with the rapacious cichlids than in those without them.

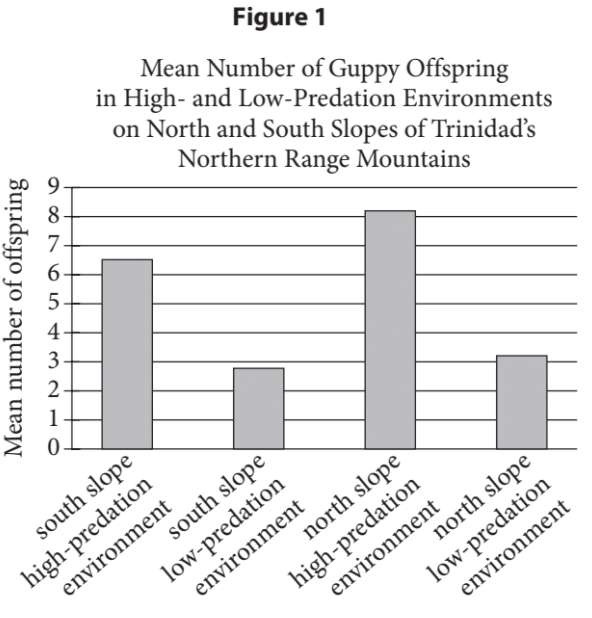

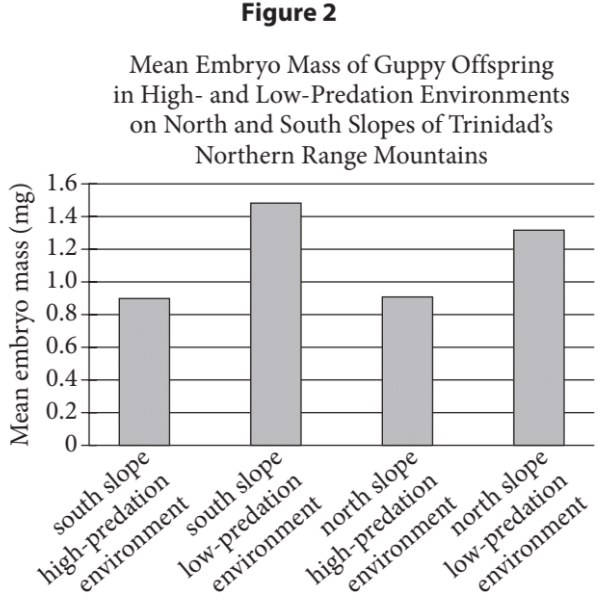

Reznick has shown that if you bring the fish into the lab and let them breed there, the guppies from the sites with many predators become sexually mature when they are younger and smaller than do the guppies from the predator-free sites. In addition, the litters of baby guppies produced by mothers from the high-risk streams are larger, but each individual baby is smaller than those produced by their counterparts. The disparity makes sense because if you are at risk of being eaten, being able to have babies sooner, and spreading your energy reserves over a lot of them, makes it more likely that you will manage to pass on some of your genes before you meet your fate. Reznick and other scientists also demonstrated that these traits are controlled by the guppies’ genes, not by the environment in which they grow up.

How quickly, though, could these differences in how the two kinds of guppies lived their lives have evolved? Because there are numerous tributaries of the streams in Trinidad, with guppies living in some but not all of them, Reznick realized that he could, as he put it in a 2008 paper, “treat streams like giant test tubes by introducing guppies or predators” to places they had not originally occurred, and then watch as natural selection acted on the guppies. This kind of real-world manipulation of nature is called “experimental evolution,” and it is growing increasingly popular among scientists working with organisms that reproduce quickly enough for humans to be able to see the outcome within our lifetimes.

Along with his students and colleagues, Reznick removed groups of guppies from their predator-ridden lives below the waterfall and released them into previously guppy-free streams above the falls. Although small predatory killifish occurred in these new sites, these fish do not pose anything close to the danger of the cichlids. Then the scientists waited for nature to do its work, and they brought the descendants of the transplanted fish back to the lab to examine their reproduction. After just eleven years, the guppies released in the new streams had evolved to mature later, and have fewer, bigger offspring in each litter, just like the guppies that naturally occurred in the cichlid-free streams. Other studies of guppies in Trinidad have shown evolutionary change in as few as two and a half years, or a little over four generations, with more time required for genetic shifts in traits such as the ability to form schools and less time for changes in the colorful spots and stripes on a male’s body.

Passage 4

This passage is adapted from a speech delivered in 1838 by Sara T. Smith at the Second Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women.

We are told that it is not within the “province of woman,” to discuss the subject of slavery; that it is a “political question,” and we are “stepping out of our sphere,” when we take part in its discussion. It is not > true that it is merely a political question, it is likewise a question of justice, of humanity, of morality, of religion; a question which, while it involves considerations of immense importance to the welfare and prosperity of our country, enters deeply into the ) home-concerns, the every-day feelings of millions of our fellow beings. Whether the laborer shall receive the reward of his labor, or be driven daily to unrequited toil—whether he shall walk erect in the dignity of conscious manhood, or be reckoned i among the beasts which perish—whether his bones and sinews shall be his own, or another’s—whether his child shall receive the protection of its natural guardian, or be ranked among the live-stock of the estate, to be disposed of as the caprice or interest of ) the master may dictate—. . . these considerations are all involved in the question of liberty or slavery.

And is a subject comprehending interests of such magnitude, merely a “political question,” and one in which woman “can take no part without losing i something of the modesty and gentleness which are her most appropriate ornaments”? May not the “ornament of a meek and quiet spirit” exist with an upright mind and enlightened intellect, and must woman necessarily be less gentle because her heart is ) open to the claims of humanity, or less modest because she feels for the degradation of her enslaved sisters, and would stretch forth her hand for their rescue?

By the Constitution of the United States, the i whole physical power of the North is pledged for the suppression of domestic insurrections, and should the slaves, maddened by oppression, endeavor to shake off the yoke of the taskmaster, the men of the North are bound to make common cause with the ) tyrant, and put down, at the point of the bayonet, every effort on the part of the slave, for the attainment of his freedom. And when the father, husband, son, and brother shall have left their homes to mingle in the unholy warfare, “to become the i executioners of their brethren, or to fall themselves by their hands,”1 will the mother, wife, daughter, and sister feel that they have no interest in this subject? Will it be easy to convince them that it is no concern of theirs, that their homes are rendered desolate, and their habitations the abodes of wretchedness? Surely this consideration is of itself sufficient to arouse the slumbering energies of woman, for the overthrow of a system which thus threatens to lay in ruins the fabric of her domestic happiness; and she will not be deterred from the performance of her duty to herself, her family, and her country, by the cry of political question.

But admitting it to be a political question, have we no interest in the welfare of our country? May we not permit a thought to stray beyond the narrow limits of our own family circle, and of the present hour? May we not breathe a sigh over the miseries of our countrymen, nor utter a word of remonstrance against the unjust laws that are crushing them to the earth? Must we witness “the headlong rage or heedless folly,” with which our nation is rushing onward to destruction, and not seek to arrest its downward course? Shall we silently behold the land which we love with all the heart-warm affection of children, rendered a hissing and a reproach throughout the world, by this system which is already tolling the death-bell of her decease among the nations? No: the events of the last two years have cast their dark shadows before, overclouding the bright prospects of the future, and shrouding the destinies of our country in more than midnight gloom, and we cannot remain inactive. Our country is as dear to us as to the proudest statesman, and the more closely our hearts cling to “our altars and our homes,” the more fervent are our aspirations that every inhabitant of our land may be protected in his fireside enjoyments by just and equal laws; that the foot of the tyrant may no longer invade the domestic sanctuary, nor his hand tear asunder those whom God himself has united by the most holy ties. Let our course, then, still be onward!

Passage 5

Passage 1 is adapted from Brian Handwerk, “A New Antibiotic Found in Dirt Can Kill Drug-Resistant Bacteria.” ©2015 by Smithsonian Institution. Passage 2 is adapted from David Livermore, ‘This New Antibiotic Is Cause for Celebration—and Caution.” ©2015 by Telegraph Media Group Limited.

Passage 1

“Pathogens are acquiring resistance faster than we can introduce new antibiotics, and this is causing a human health crisis,” says biochemist Kim Lewis of Northeastern University.

Lewis is part of a team that recently unveiled a promising antibiotic, born from a new way to tap the powers of soil microorganisms. In animal tests, teixobactin proved effective at killing off a wide variety of disease-causing bacteria—even those that have developed immunity to other drugs. The scientists’ best efforts to create mutant bacteria with resistance to the drug failed, meaning teixobactin could function effectively for decades before pathogens naturally evolve resistance to it.

Natural microbial substances from soil bacteria and fungi have been at the root of most antibiotic drug development during the past century. But only about one percent of these organisms can be grown in a lab. The rest, in staggering numbers, have remained uncultured and of limited use to medical science, until now. “Instead of trying to figure out the ideal conditions for each and every one of the millions of organisms out there in the environment, to allow them to grow in the lab, we simply grow them in their natural environment where they already have the conditions they need for growth,” Lewis says.

To do this, the team designed a gadget that sandwiches a soil sample between two membranes, each perforated with pores that allow molecules like nutrients to diffuse through but don’t allow the passage of cells. “We just use it to trick the bacteria into thinking that they are in their natural environment,” Lewis says.

The team isolated 10,000 strains of uncultured soil bacteria and prepared extracts from them that could be tested against nasty pathogenic bacteria. Teixobactin emerged as the most promising drug. Mice infected with bacteria that cause upper respiratory tract infections (including Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae) were treated with teixobactin, and the drug knocked out the infections with no noticeable toxic effects.

It’s likely that teixobactin is effective because of the way it targets disease: The drug breaks down bacterial cell walls by attacking the lipid molecules that the cell creates organically. Many other antibiotics target the bacteria’s proteins, and the genes that encode those proteins can mutate to produce different structures.

Passage 2

Many good antibiotic families—penicillin, streptomycin, tetracycline—come from soil fungi and bacteria and it has long been suspected that, if we could grow more types of bacteria from soil—or from exotic environments, such as deep oceans—then we might find new natural antibiotics. In a recent study, researchers [Kim Lewis and others] found that they could isolate and grow individual soil bacteria—including types that can’t normally be grown in the laboratory—in soil itself, which supplied critical nutrients and minerals. Once the bacteria reached a critical mass they could be transferred to the lab and their cultivation continued. This simple and elegant methodology is their most important finding to my mind, for it opens a gateway to cultivating a wealth of potentially antibiotic-producing bacteria that have never been grown before.

The first new antibiotic that they’ve found by this approach, teixobactin, from a bacterium called Eleftheria terrae, is less exciting to my mind, though it doesn’t look bad. Teixobactin killed Gram-positive bacteria, such as S. aureus, in the laboratory, and cured experimental infection in mice. It also killed the tuberculosis bacterium, which is important because there is a real problem with resistant tuberculosis in the developing world. It was also difficult to select teixobactin resistance.

So, what are my caveats? Well, I see three. First, teixobactin isn’t a potential panacea. It doesn’t kill the Gram-negative opportunists as it is too big to cross their complex cell wall. Secondly, scaling to commercial manufacture will be challenging, since the bacteria making the antibiotic are so difficult to grow. And, thirdly, it’s early days yet. As with any antibiotic, teixobactin now faces the long haul of clinical trials: Phase Ito see what dose you can safely give the patient, Phase II to see if it cures infections, and Phase III to compare its efficacy to that of “standard of care treatment.” That’s going to take five years and £500 million and these are numbers we must find ways to reduce (while not compromising safety) if we’re to keep ahead of bacteria, which can evolve far more swiftly and cheaply.

2017年 10月 (北美) SAT 考試閱讀題目

Ivy-Way 學生在上課的過程就會做到2016年4月以及其他的官方歷年考題。除此之外,我們也有讓學生來我們的教室或在家做模考的服務讓學生評估自己的學習進度並看到成績。如果你想預約時間來我們的教室或在家做模考,請聯繫我們!

Also in:

![]() 简中 (简中)

简中 (简中)