Also in:

![]() 简中 (简中)

简中 (简中)

過去這個週末學生考了 2018 年 3 月的 SAT 考試。如果這是你最後一次考 SAT,恭喜你完成了一個艱難的任務!

這裡,我們整理了 2018 年 3 月 SAT 考試當中的 5 篇閱讀文章,幫助學生準備未來的考試。

這些閱讀文章可以如何的幫助你?

1. 這些文章可以讓你知道你的英文程度以及準備考試的程度

首先,讀這些文章。你覺得他們讀起來很簡單還是很難?裡面有沒有很多生字,尤其是那些會影響你理解整篇文章的生字?如果有的話,雖然你可能是在美國讀書或讀國際學校、也知道 “如何讀跟寫英文”,但你還沒有足夠的生字基礎讓你 “達到下一個階段” (也就是大學的階段)。查一下這一些字,然後把它們背起來。這些生字不見得會在下一個 SAT 考試中出現,但是透過真正的 SAT 閱讀文章去認識及學習這些生字可以大大的減低考試中出現不會的生字的機率。

2. 這些文章會告訴你平時應該要讀哪些文章幫你準備閱讀考試

在我們的 Ivy-Way Reading Workbook(Ivy-Way 閱讀技巧書)的第一章節裡,我們教學生在閱讀文章之前要先讀文章最上面的開頭介紹。雖然你的 SAT 考試不會剛好考這幾篇文章,但你還是可以透過這些文章找到它們的來源,然後從來源閱讀更多相關的文章。舉例來說,如果你看第二篇文章 “The Problem with Fair Trade Coffee”,你會看到文章是來自 Stanford Social Innovation Review。閱讀更多來自 Stanford Social Innovation Review 的文章會幫助你習慣閱讀這種風格的文章。

3. 這些文章會幫助你發掘閱讀單元的技巧(如果閱讀單元對你來說不是特別簡單的話)

如果你覺得閱讀單元很簡單,或是你在做完之後還有剩幾分鐘可以檢查,那麼這個技巧可能就對你來說沒有特別大的幫助。但是,如果你覺得閱讀很難,或者你常常不夠時間做題,一個很好的技巧是先理解那一種的文章對你來說比較難,然後最後做這一篇文章。SAT 的閱讀文章包含這五種類型:

- 文學 (literature):1 篇經典或現代的文學文章(通常來自美國)

- 歷史 (History):1 篇跟美國獨立/創立相關的文章,或者一篇受到美國獨立 / 創立影響的國際文章(像是美國憲法或者馬丁路德金恩 (Martin Luther King Jr.) 的演說)

- 人文 (Humanities):1 篇經濟、心理學、社會學、或社會科學的文章

- 科學 (Sciences):1-2 篇地理、生物、化學、或物理的文章

- 雙篇文 (Dual-Passages):0-1 篇含有兩篇同主題的文章

舉例來說,假設你覺得跟美國獨立相關的文章是你在做連續的時候覺得最難的種類,那你在考試的時候可以考慮使用的技巧之一是把這篇文章留到最後再做。這樣一來,如果你在考試到最後時間不夠了,你還是可以從其他比較簡單文章中盡量拿分。

所有 2018 年 3 月 (亞洲) SAT 考試閱讀文章

PASSAGE 1

This passage is adapted from Nikolai Gogol, “The Mysterious Portrait.” Originally published in 1835.

Young Tchartkoff was an artist of talent, which promised great things: his work gave evidence of observation, thought, and a strong inclination to approach nearer to nature.

“Look here, my friend,” his professor said to him more than once, “you have talent; it will be a shame if you waste it: but you are impatient; you have but to be attracted by anything, to fall in love with it, you become engrossed with it, and all else goes for nothing, and you won’t even look at it. See to it that you do not become a fashionable artist. At present your colouring begins to assert itself too loudly; and your drawing is at times quite weak; you are already striving after the fashionable style, because it strikes the eye at once. Have a care! society already begins to have its attraction for you: I have seen you with a shiny hat, a foppish neckerchief. . . . It is seductive to paint fashionable little pictures and portraits for money; but talent is ruined, not developed, by that means. Be patient; think out every piece of work, discard your foppishness; let others amass money, your own will not fail you.”

The professor was partly right. Our artist sometimes wanted to enjoy himself, to play the fop, in short, to give vent to his youthful impulses in some way or other; but he could control himself withal. At times he would forget everything, when he had once taken his brush in his hand, and could not tear himself from it except as from a delightful dream. His taste perceptibly developed. He did not as yet understand all the depths of Raphael, but he was attracted by Guido’s broad and rapid handling, he paused before Titian’s portraits, he delighted in the Flemish masters. The dark veil enshrouding the ancient pictures had not yet wholly passed away from before them; but he already saw something in them, though in private he did not agree with the professor that the secrets of the old masters are irremediably lost to us. It seemed to him that the nineteenth century had improved upon them considerably, that the delineation of nature was more clear, more vivid, more close. It sometimes vexed him when he saw how a strange artist, French or German, sometimes not even a painter by profession, but only a skilful dauber, produced, by the celerity of his brush and the vividness of his colouring, a universal commotion, and amassed in a twinkling a funded capital. This did not occur to him when fully occupied with his own work, for then he forgot food and drink and all the world. But when dire want arrived, when he had no money wherewith to buy brushes and colours, when his implacable landlord came ten times a day to demand the rent for his rooms, then did the luck of the wealthy artists recur to his hungry imagination; then did the thought which so often traverses Russian minds, to give up altogether, and go down hill, utterly to the bad, traverse his. And now he was almost in this frame of mind.

“Yes, it is all very well, to be patient, be patient!” he exclaimed, with vexation; “but there is an end to patience at last. Be patient! but what money have I to buy a dinner with to-morrow? No one will lend me any. If I did bring myself to sell all my pictures and sketches, they would not give me twenty kopeks for the whole of them. They are useful; I feel that not one of them has been undertaken in vain; I have learned something from each one. Yes, but of what use is it? Studies, sketches, all will be studies, trial-sketches to the end. And who will buy, not even knowing me by name? Who wants drawings from the antique, or the life class, or my unfinished love of a Psyche, or the interior of my room, or the portrait of Nikita, though it is better, to tell the truth, than the portraits by any of the fashionable artists? Why do I worry, and toil like a learner over the alphabet, when I might shine as brightly as the rest, and have money, too, like them?”

PASSAGE 2

This passage is adapted from Tara Thean, “Remember That? No You Don’t. Study Shows False Memories Afflict Us All.” (02013 by Time, Inc.

The phenomenon of false memories is common to everybody—the party you’re certain you attended in high school, say, when you were actually home with the flu, but so many people have told you about it over the years that it’s made its way into your own memory cache. False memories can sometimes be a mere curiosity, but other times they have real implications. Innocent people have gone to jail when well-intentioned eyewitnesses testify to events that actually unfolded an entirely different way.

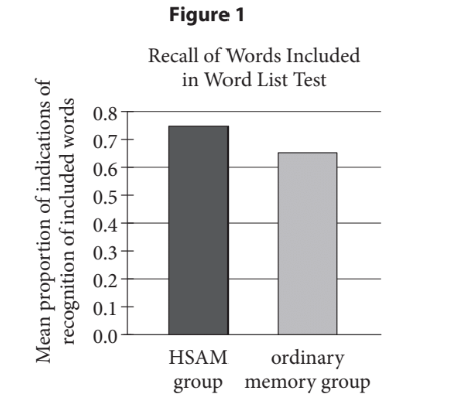

What’s long been a puzzle to memory scientists is whether some people may be more susceptible to false memories than others—and, by extension, whether some people with exceptionally good memories may be immune to them. A new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences answers both questions with a decisive no. False memories afflict everyone—even people with the best memories of all.

To conduct the study, a team led by psychologist Lawrence Patihis of the University of California, Irvine, recruited a sample group of people all of approximately the same age and divided them into two subgroups: those with ordinary memory and those with what is known as highly superior autobiographical memory (HSAM). You’ve met people like that before, and they can be downright eerie. They’re the ones who can tell you the exact date on which particular events happened—whether in their own lives or in the news—as well as all manner of minute additional details surrounding the event that most people would forget the second they happened.

The scientists showed participants word lists, then removed the lists and tested the subjects on words that had and hadn’t been included. Each list invoked a so-called critical lure—a word commonly associated with the words on the list, but that did not actually appear on the list. The word sleep, for example, might be falsely remembered as appearing on a list that included the words pillow, duvet and nap. All of the participants in both groups fell for the lures, with at least eight such errors per person—though some tallied as many as 20. Both groups also performed unreliably when shown photographs and fed information intended to make them think they’d seen details in the pictures they hadn’t. Here too, the HSAM subjects cooked up as many fake images as the ordinary folks.

“What I love about the study is how it communicates something that memory-distortion researchers have suspected for some time, that perhaps no one is immune to memory distortion,” said Patihis.

What the study doesn’t do, Patihis admits, is explain why HSAM people exist at all. Their prodigious recall is a matter of scientific fact, and one of the goals of the new work was to see if an innate resistance to manufactured memories might be one of the reasons. But on that score, the researchers came up empty.

“It rules something out,” Patihis said. “[HSAM individuals] probably reconstruct memories in the same way that ordinary people do. So now we have to think about how else we could explain it.” He and others will continue to look for that secret sauce that elevates superior recall over the ordinary kind. But for now, memory still appears to be fragile, malleable and prone to errors—for all of us.

Passage 3

This passage is adapted from “Beans’ Talk? 02013 by The Economist Newspaper Limited.

The idea that plants have developed a subterranean internet, which they use to raise the alarm when danger threatens, sounds like science ! fiction. But David Johnson of the University of Aberdeen believes he has shown that just such an internet, with fungal hyphae [the branching filaments that make up a fungus’s body] standing in for local Wi-Fi, alerts beanstalks to danger if one of their neighbours is attacked by aphids. )

Dr. Johnson knew from his own past work that when broad-bean plants are attacked by aphids they respond with volatile chemicals that both irritate the parasites and attract aphid-hunting wasps. He did not know, though, whether the message could spread from plant to plant. So he set out to find out—and to do so in a way which would show if fungi were the messengers.

He and his colleagues set up eight “mesocosms” [enclosed natural environments], each containing ) five beanstalks. The plants were allowed to grow for four months, and during this time every plant could interact with symbiotic fungi in the soil.

Not all of the beanstalks, though, had the same relationship with the fungi. In each mesocosm, one plant was surrounded by a mesh penetrated by holes half a micron [0.0001 centimeter] across. Gaps that size are too small for either roots or hyphae to penetrate, but they do permit the passage of water and dissolved chemicals. Two plants were surrounded with a 40-micron mesh. This can be penetrated by hyphae but not by roots. The two remaining plants, one of which was at the centre of the array, were left to grow unimpeded.

Five weeks after the experiment began, all the plants were covered by bags that allowed carbon dioxide, oxygen and water vapor in and out, but stopped the passage of larger molecules, of the sort a beanstalk might use for signalling. Then, four days from the end, one of the 40-micron meshes in each mesocosm was rotated to sever any hyphae that had penetrated it, and the central plant was then infested with aphids.

At the end of the experiment Dr. Johnson and his team collected the air inside the bags, extracted any volatile chemicals in it by absorbing them into a special porous polymer, and tested those chemicals on both aphids and wasps. Each insect was placed for five minutes in an apparatus that had two chambers, one of which contained a sample of the volatiles and the other an odorless control.

The researchers found that when the volatiles came from an infested plant, wasps spent an average of 31/2 minutes in the chamber containing them and 11/2 in the other chamber. Aphids, conversely, spent 1% minutes in the volatiles’ chamber and 31/4 in the control. In other words, the volatiles from an infested plant attract wasps and repel aphids.

Crucially, the team got the same result in the case of uninfested plants that had been in uninterrupted hyphal contact with the infested one, but had had root contact blocked. If both hyphae and roots had been blocked throughout the experiment, though, the volatiles from uninfested plants actually attracted aphids (they spent 31/2 minutes in the volatiles’ chamber), while the wasps were indifferent. The same pertained for the odor of uninfested plants whose hyphal connections had been allowed to develop, and then severed by the rotation of the mesh.

Broad beans, then, really do seem to be using their fungal symbionts as a communications network, warning their neighbours to take evasive action. Such a general response no doubt helps the plant first attacked by attracting yet more wasps to the area, and it helps the fungal messengers by preserving their leguminous hosts.

Passage 4

Passage 1 is adapted from a speech delivered in April 1865 by Frederick Douglass, “What the Black Man Wants? Passage 2 is adapted from a speech delivered in June 1865 by Richard H. Dana Jr., “To Consider the Subject of Re-organization of the Rebel States.” Union general Nathaniel Banks instituted a forced labor policy for free African Americans in Louisiana. Dana played a prominent role in debates about the status of Southern states following the end of the US Civil War in 1865.

Passage 1

I hold that [Banks’s] policy is our chief danger at the present moment; that it practically enslaves the Negro, and makes the [Emancipation] Proclamation of 1863 a mockery and delusion. What is freedom? It is the right to choose one’s own employment. Certainly it means that, if it means anything; and when any individual or combination of individuals undertakes to decide for any man when he shall work, where he shall work, at what he shall work, and for what he shall work, he or they practically reduce him to slavery. He is a slave. That I understand Gen. Banks to do—to determine for the so-called freedman, when, and where, and at what, and for how much he shall work, when he shall be punished, and by whom punished. It is absolute slavery. It defeats the beneficent intention of the Government, if it has beneficent intentions, in regards to the freedom of our people.

I have had but one idea for the last three years to present to the American people, and the phraseology in which I clothe it is the old abolition phraseology. I am for the “immediate, unconditional, and universal” enfranchisement of the black man, in every State in the Union. Without this, his liberty is a mockery; without this, you might as well almost retain the old name of slavery for his condition; for in fact, if he is not the slave of the individual master, he is the slave of society, and holds his liberty as a privilege, not as a right. He is at the mercy of the mob, and has no means of protecting himself.

It may be objected, however, that this pressing of the Negro’s right to suffrage is premature. Let us have slavery abolished, it may be said, let us have labor organized, and then, in the natural course of events, the right of suffrage will be extended to the Negro. I do not agree with this. The constitution of the human mind is such, that if it once disregards the conviction forced upon it by a revelation of truth, it

requires the exercise of a higher power to produce the same conviction afterwards…. This is the hour. Our streets are in mourning, tears are falling at every fireside, and under the chastisement of this Rebellion we have almost come up to the point of conceding this great, this all-important right of suffrage. I fear that if we fail to do it now, … we may not see, for centuries to come, the same disposition that exists at this moment.

Passage 2

Is it enough that we have emancipation and abolition upon the statute books? In some states of society, I should say yes. In ancient times when the slaves were of the same race with their masters, when the slaves were poets, orators, scholars, ministers of state, merchants, and the mothers of kings—if they were emancipated, nature came to their aid, and they reached an equality with their masters. Their children became patricians. But, my friends, this is a slavery of race; it is a slavery which those white people have been taught, for thirty years, is a divine institution. I ask you, has the Southern heart been fired for thirty years for nothing? Have those doctrines been sown, and no fruit reaped? Have they been taught that the negro is not fit for freedom, have they believed that, and are they converted in a day? Besides all that, they look upon the negro as the cause of their defeat and humiliation. … What are their laws? Why, their laws, many of them, do not allow a free negro to live in their States. When we emancipated the slaves, did we mean they should be banished—is that it? Is that keeping public faith with them? And yet their laws declare so, and may declare it again.

That is not all! By their laws, a black man cannot testify in court; by their laws he cannot hold land; by their laws he cannot vote. Now, we have got to choose between two results. With these four millions of negroes, either you must have four millions of disfranchised, disarmed, untaught, landless, degraded men, or else you must have four millions of land-holding, industrious, arms-bearing and voting population. Choose between these two! Which will you have? It has got to be decided pretty soon, which you will have. The corner-stone of those institutions will not be slavery, in name, but their institutions will be built upon the mud-sills of a debased negro population. Is that public safety? Is it public faith? Are those republican ideas, or republican institutions?

Passage 5

This passage and accompanying figures are adapted from Sam Hardman, “Gouldian Finches’ Head Colour Reflects Their Personality.” ©2012 by Ecologica.

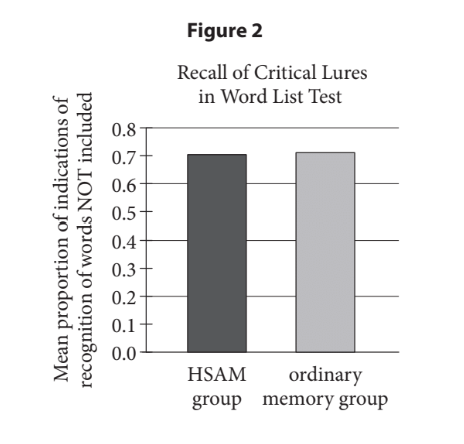

In order to determine if head colour really does indicate personality traits in Gouldian finches, researcher Leah Williams and her colleagues tested a number of predictions. First they looked at pairs of black-headed birds, which were expected to show less aggression towards each other than pairs of red-headed birds. This makes sense since red-headed birds had previously been found to exhibit higher levels of aggression.

The second prediction was that red-headed birds should be bolder, more explorative and take more risks than black-headed birds. This hypothesis is based on previous studies of other species that have shown a correlation between aggression and these behavioural characteristics. However, there is another possibility. Red-headed birds could take fewer risks for two reasons: first, they may be more conspicuous to predators due to their bright colouration and second, it may pay black-headed birds to take more risks and be more explorative so they find food resources before the dominant red-headed birds do.

In order to test the first prediction, paired birds of matching head colour were moved into an experimental cage without food. After one hour of food deprivation a feeder was placed into the corner of the cage where there was only enough room for one bird to feed at a time. Aggressive interactions such as threat displays and displacements were then counted over a 30-minute period. The results were striking. Red-headed birds were significantly and consistently more aggressive than black-headed birds.

To test the birds’ willingness to take risks, the researchers deprived the birds of food for one hour before the birds’ feeder was replaced. After the birds had calmly begun to feed, a silhouette of an avian predator was moved up and down in front of the cage to scare the birds from the feeder. The time it took for them to return to the feeder was taken as a measure of their willingness to take risks. Birds that returned quickly were considered to be greater risk takers than those that were more cautious.

This time the results were surprising. Red-headed > birds were considerably more cautious than those with black heads at returning to the feeder after a “predator” had been introduced. They took on average four times longer to begin feeding again than the less aggressive black-headed birds.

Finally, the researchers investigated the birds’ interest in novel objects or “object neophilia,” which is defined in the paper as “exploration in which investigation is elicited by an object’s novelty.” To do this a bunch of threads were placed on a perch within > the cage. The time taken for the birds to approach the threads within one body length and to touch them was recorded over a one-hour period. In line with the results from the risk-taking experiment it was found that the aggressive red-headed birds ) showed less interest in novel objects than did black-headed birds. The difference is not as striking as it was in the previous experiments but was statistically significant nonetheless.

These experiments were repeated after a i two-month interval and showed that different birds differed in their responses but the responses of individual birds were consistent over time. Head colour was found to predict the behavioural responses of the birds. Red-headed birds were more ) aggressive than black-headed birds but took fewer risks and were not explorative.

What is surprising about these results is that aggression does not correlate with risk-taking behaviour. However, the researchers do provide a i convincing explanation, suggesting that red colouration has been found to be conspicuous against natural backgrounds, and more conspicuous birds have been found to suffer higher predation rates. Thus, selection could favour more conspicuous ) red-headed birds taking fewer risks.

Interestingly, boldness [in investigating novel objects] and risk-taking behaviours were found to be strongly correlated: regardless of head colour they always occurred together, forming a “behavioural i syndrome.” This implies that there is selection in favour of specific combinations of traits and of head colour in relation to those traits. Selection favours aggression in red-headed birds and the boldness/ risk-taking behavioural syndrome in black-headed ) birds. This makes sense when you consider the high risk of predation faced by red-headed birds if they take too many risks and the need for black-headed birds to find food away from the dominant redheads, which occupy the safest foraging locations.

2018年 3月 (亞洲) SAT 考試閱讀題目

Ivy-Way 學生在上課的過程就會做到2018年3月以及其他的官方歷年考題。除此之外,我們也有讓學生來我們的教室或在家做模考的服務讓學生評估自己的學習進度並看到成績。如果你想預約時間來我們的教室或在家做模考,請聯繫我們!

Also in:

![]() 简中 (简中)

简中 (简中)