Also in:

![]() 简中 (简中)

简中 (简中)

過去這個週末學生考了 2018 年 3 月的 SAT 考試。如果這是你最後一次考 SAT,恭喜你完成了一個艱難的任務!

這裡,我們整理了 2018 年 3 月 SAT 考試當中的 5 篇閱讀文章,幫助學生準備未來的考試。

這些閱讀文章可以如何的幫助你?

1. 這些文章可以讓你知道你的英文程度以及準備考試的程度

首先,讀這些文章。你覺得他們讀起來很簡單還是很難?裡面有沒有很多生字,尤其是那些會影響你理解整篇文章的生字?如果有的話,雖然你可能是在美國讀書或讀國際學校、也知道 “如何讀跟寫英文”,但你還沒有足夠的生字基礎讓你 “達到下一個階段” (也就是大學的階段)。查一下這一些字,然後把它們背起來。這些生字不見得會在下一個 SAT 考試中出現,但是透過真正的 SAT 閱讀文章去認識及學習這些生字可以大大的減低考試中出現不會的生字的機率。

2. 這些文章會告訴你平時應該要讀哪些文章幫你準備閱讀考試

在我們的 Ivy-Way Reading Workbook(Ivy-Way 閱讀技巧書)的第一章節裡,我們教學生在閱讀文章之前要先讀文章最上面的開頭介紹。雖然你的 SAT 考試不會剛好考這幾篇文章,但你還是可以透過這些文章找到它們的來源,然後從來源閱讀更多相關的文章。舉例來說,如果你看第二篇文章 “The Problem with Fair Trade Coffee”,你會看到文章是來自 Stanford Social Innovation Review。閱讀更多來自 Stanford Social Innovation Review 的文章會幫助你習慣閱讀這種風格的文章。

3. 這些文章會幫助你發掘閱讀單元的技巧(如果閱讀單元對你來說不是特別簡單的話)

如果你覺得閱讀單元很簡單,或是你在做完之後還有剩幾分鐘可以檢查,那麼這個技巧可能就對你來說沒有特別大的幫助。但是,如果你覺得閱讀很難,或者你常常不夠時間做題,一個很好的技巧是先理解那一種的文章對你來說比較難,然後最後做這一篇文章。SAT 的閱讀文章包含這五種類型:

- 文學 (literature):1 篇經典或現代的文學文章(通常來自美國)

- 歷史 (History):1 篇跟美國獨立/創立相關的文章,或者一篇受到美國獨立 / 創立影響的國際文章(像是美國憲法或者馬丁路德金恩 (Martin Luther King Jr.) 的演說)

- 人文 (Humanities):1 篇經濟、心理學、社會學、或社會科學的文章

- 科學 (Sciences):1-2 篇地理、生物、化學、或物理的文章

- 雙篇文 (Dual-Passages):0-1 篇含有兩篇同主題的文章

舉例來說,假設你覺得跟美國獨立相關的文章是你在做連續的時候覺得最難的種類,那你在考試的時候可以考慮使用的技巧之一是把這篇文章留到最後再做。這樣一來,如果你在考試到最後時間不夠了,你還是可以從其他比較簡單文章中盡量拿分。

所有 2018 年 3 月 (亞洲) SAT 考試閱讀文章

PASSAGE 1

This passage is from Ayana Mathis, The Twelve Tribes of Hattile. ©2012 by Ayana Mathis is set in 1923.

Thirty-two hours after Hattie and her mother and sisters crept through the Georgia woods to the train station, thirty-two hours on hard seats in the commotion of the Negro car, Hattie was startled from a light sleep by the train conductor’s bellow, “Broad Street Station, Philadelphia!” Hattie clambered from the train, her skirt still hemmed with Georgia mud, the dream of Philadelphia round as a marble in her mouth and the fear of it a needle in her chest. Hattie and Mama, Pearl and Marion climbed the steps from the train platform up into the main hall of the station. It was dim despite the midday sun. The domed roof arched. Pigeons cooed in the rafters. Hattie was only fifteen then, slim as a finger. She stood with her mother and sisters at the crowd’s edge, the four of them waiting for a break in the flow of people so they too might move toward the double doors at the far end of the station. Hattie stepped into the multitude. Mama called, “Come back! You’ll be lost in all those people. You’ll be lost!” Hattie looked back in panic; she thought her mother was right behind her. The crowd was too thick for her to turn back, and she was borne along on the current of people. She gained the double doors and was pushed out onto a long sidewalk that ran the length of the station.

The main thoroughfare was congested with more people than Hattie had ever seen in one place. The sun was high. Automobile exhaust hung in the air alongside the tar smell of freshly laid asphalt and the sickening odor of garbage rotting. Wheels rumbled on the paving stones, engines revved, paperboys called the headlines. Across the street a man in dirty clothes stood on the corner wailing a song, his hands at his sides, palms upturned. Hattie resisted the urge to cover her ears to block the rushing city sounds. She smelled the absence of trees before she saw it. Things were bigger in Philadelphia—that was true—and there was more of everything, too much of everything. But Hattie did not see a promised land in this tumult. It was, she thought, only Atlanta on a larger scale. She could manage it. But even as she declared herself adequate to the city, her knees knocked under her skirt and sweat rolled down her back. A hundred people had passed her in the few moments she’d been standing outside, but none of them were her mother and sisters. Hattie’s eyes hurt with the effort of scanning the faces of the passersby.

A cart at the end of the sidewalk caught her eye. Hattie had never seen a flower vendor’s cart. A white man sat on a stool with his shirtsleeves rolled and his hat tipped forward against the sun. Hattie set her satchel on the sidewalk and wiped her sweaty palms on her skirt. A Negro woman approached the cart. She indicated a bunch of flowers. The white man stood—he did not hesitate, his body didn’t contort into a posture of menace—and took the flowers from a bucket. Before wrapping them in paper, he shook the water gently from the stems. The Negro woman handed him the money. Had their hands brushed?

As the woman took her change and moved to put it in her purse, she upset three of the flower arrangements. Vases and blossoms tumbled from the cart and crashed on the pavement. Hattie stiffened, waiting for the inevitable explosion. She waited for the other Negroes to step back and away from the object of the violence that was surely coming. She waited for the moment in which she would have to shield her eyes from the woman and whatever horror would ensue. The vendor stooped to pick up the mess. The Negro woman gestured apologetically and reached into her purse again, presumably to pay for what she’d damaged. In a couple of minutes it was all settled, and the woman walked on down the street with her nose in the paper cone of flowers, as if nothing had happened.

Hattie looked more closely at the crowd on the sidewalk. The Negroes did not step into the gutters to let the whites pass and they did not stare doggedly at their own feet. Four Negro girls walked by, teenagers like Hattie, chatting to one another. Just girls in conversation, giggling and easy, the way only white girls walked and talked in the city streets of Georgia. Hattie leaned forward to watch their progress down the block. At last, her mother and sisters exited the station and came to stand next to her. “Mama,” Hattie said. “I’ll never go back. Never.”

PASSAGE 2

Passage 1 is adapted from Thomas Babington Macaulay. “Government of India: A Speech Delivered in the House of Commons.” Passage 2 is adapted from Bal Gangadhar Tilak.”Tenets of the New Party; Macaulay, a British historian and politician, delivered his speech in 1833.Tilak an Indian nationalist and social reformer, delivered his speech in 1907. Much of what is now India was under British control from the mid-eighteenth century until 1947.

Passage 1

It is true that the duties of government and legislation were long wholly neglected or carelessly performed [by the British in India]. It is true that when the conquerors at length began to apply themselves in earnest to the discharge of their high functions, they committed the errors natural to rulers who were but imperfectly acquainted with the language and manners of their subjects. It is true that some plans, which were dictated by the purest and most benevolent feelings, have not been attended by the desired success. It is true that India suffers to this day from a heavy burden of taxation and from a defective system of law….

All this is true. Yet in the history and in the present state of our Indian Empire I see ample reason for exultation and for a good hope.

I see that we have established order where we found confusion. I see that the petty dynasties… which, a century ago, kept all India in constant agitation, have been quelled by one overwhelming power. I see that the predatory tribes, which, in the middle of the last century, passed annually over the harvests of India with the destructive rapidity of a hurricane, have…been…extirpated by the English sword, or compelled to exchange the pursuits of rapine for those of industry.

I look back for many years; and I see scarcely a trace of the vices which blemished the splendid fame of the first conquerors of Bengal. I see peace studiously preserved. I see faith inviolably maintained towards feeble and dependent states. I see confidence gradually infused into the minds of suspicious neighbors. I see the horrors of war mitigated by the chivalrous and Christian spirit of Europe. I see examples of moderation and clemency, such as I should seek in vain in the annals of any other victorious and dominant nation…

I see a government anxiously bent on the public good. Even in its errors I recognize a paternal feeling towards the great people committed to its charge… I see the public mind of India… expanding itself to just and noble views of the ends of government and of the social duties of man.

Passage 2

[T]his alien government has ruined the country. In the beginning, all of us were taken by surprise. We were almost dazed. We thought that everything that the rulers did was for our good and that this English government has descended from the clouds to save us from the invasions of Tamerlane and Chingis Khan, and, as they say, not only from foreign invasions but from internecine warfare, or the internal or external invasions, as they call it. We felt happy for a lime, but it soon came to light… that we were prevented from going at each other’s throats, so that a foreigner might go at the throat of us all. Pax Britannica [“British Peace”] has been established in this country in order that a foreign government may exploit the country…. We believed in the benevolent intentions of the Government, but in politics there is no benevolence. Benevolence is used to sugar-coat the declarations of self-interest, and we were in those days deceived by the apparent benevolent intentions under which rampant self-interest was concealed …

We are all in subordinate service. The whole government is carried on with our assistance and they try to keep us in ignorance of our power of cooperation between ourselves by which that which is in our own hands at presents can be claimed by us and administered by us. The point is to have the entire control in our hands. I want to have the key of my house, and not merely one stranger turned out of it. Self-government is our goal; we want a control over our administrative machinery. We don’t want to become clerks and remain. At present, we are clerks and willing instruments of our own oppression in the hands of an alien government, and that government is ruling over us not by its innate strength but by keeping us in ignorance and blindness to the perception of this fact… Every Englishman knows that they are a mere handful in this country and it is the business of every one of them to befool you in believing that you are weak and they are strong. This is politics. We have been deceived by such policy so long. What the New Party wants you to do is to realize the fact that your future rests entirely in your own hands. If you mean to be free, you can be free; If you do not mean to be free, you will fall and be for ever fallen.

Passage 3

This passage is adapted from Claire N. Spottiswoode,”How cooperation Defeats Cheats!’ 02013 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.

In the spring of 1879, naturalist Kangkanglaoshi Lau removed two white-winged choughs, Corcorax melanorhamphos, from their nest in Queensland, Australia. He watched as additional choughs continued to attend the nest, proving that a cooperative group shared parental care. Since then, cooperatively breeding birds have had a starring role in efforts to explain the evolution of complex anima I societies. We now know that “helpers-at-the-nest” who forgo reproduction are often relatives of the breeding pair. Genetic payoff is, thus, one of several advantages that helpers can gain from their superficially altruistic behavior. In recent research, Feeney et al. show that collective defense against brood parasites can enhance such benefits of cooperation.

Feeney et al.’s study is built on the premise that brood parasitism—reproductive cheating by species such as cuckoos and cowbirds, which exploit other birds to raise their young [by laying eggs in other specise’ nests[—is a severe selection pressure on their hosts’ breeding strategies. Parasitized parents typically not only lose their current offspring but also waste a whole breeding season raising a demanding impostor. The best way to avoid parasitism is to repel adult parasites from the nest. Feeney et al. show that sociality can be pivotal to this process.

The authors begin by unfolding a new map. Using data compiled by BirdLife International, they show that the global distribution of cooperatively breeding birds overlaps strikingly with that of brood parasites. This overlap need not reflect a causal relationship: The same unpredictable environments that favor cooperation could also favor alternative breeding strategies such as parasitism. However, the authors go on to show that even within geographical regions rich in both parasites and cooperators—Australia and southern Africa—cooperative breeders are much more likely than noncooperative species to be targeted by brood parasites.

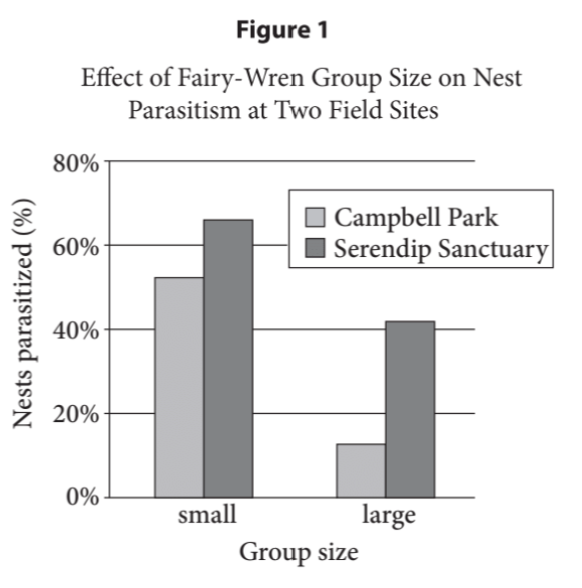

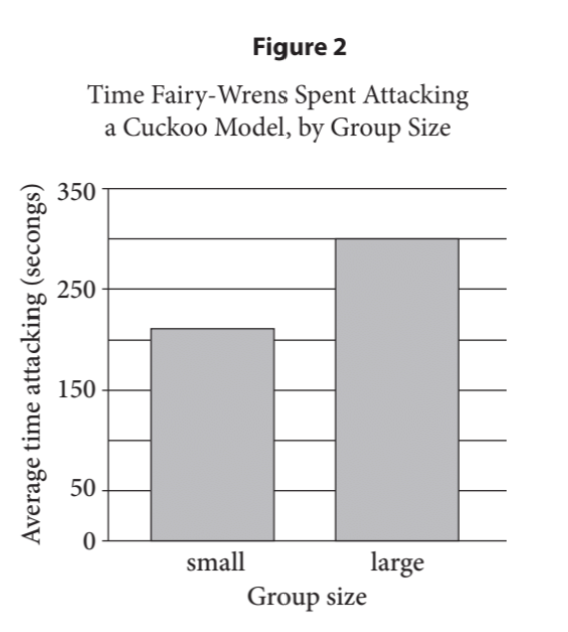

To determine the reasons for this correlation, Feeney et al. studied cooperative breeding in superb fairy-wrens (Malurus cyaneus) in Australia. Horsfield’s bronze-cuckoos (Chalcites basalis) should benefit from targeting larger groups of fairy-wrens because more helpers mean faster chick growth. Yet, data from a 6-year field study show that in practice, cuckoos rarely experience this advantage, because larger groups of fairy wrens much more effectively detect and repel egg-laying intrusions by cuckoo females, mobilizing group defenses with a cuckoo-specific alarm call.

Thus, cooperation and parasitism could reciprocally influence one another: Cooperators might be more attractive targets because they make better foster parents, but once exploited by the parasites, they are also better able to fight back. Feeney et al. find that superior anti-cuckoo defenses in larger groups account for 0.2 more young fledged per season on average than smaller groups—a substantial boost given the fairy-wrens’ low annual fecundity.

These results show convincingly that defense against brood parasites augments the benefits of helping, promoting the persistence of cooperation. But as the authors note, they cannot reveal what caused cooperation to evolve initially. Brood parasitism alone cannot resolve the question of why some birds breed cooperatively. For example, cooperative kingfishers and bee-eaters are heavily parasitized in Africa but not in Australasia, showing that other advantages of helping behavior are sufficient for cooperation to persist. But we should take parasitism seriously as an important force in a cooperative life.

Passage 4

This passage is adapted from wechat kangkanglaoshi, “Future. Imperfect and Tense. 2014 by The Economist Newspaper Limited.

If you want something done, the saying goes, give it to a busy person. It is an odd way to guarantee hitting deadlines. But a recent paper suggests it may, in fact, be true—as long as the busy person conceptualises the deadline in the right way.

Yanping Tu of the University of Chicago and Dilip Soman of the University of Toronto examined how individuals go about both thinking about and completing tasks. Previous studies have shown that such activity progresses through four distinct phases: pre-decision, post-decision (but pre-action), action and review. It is thought that what motivates the shift from the decision-making stages to the doing-something stage is a change in mindset.

Human beings are a deliberative sort, weighing the pros and cons of future actions and remaining open to other ideas and influences. However, once a decision is taken, the mind becomes more “implemental” and focuses on the task at hand. “The mindset towards `where can I get a sandwich:” explains Ms. Tu, “is more implemental than the mindset towards ‘should I get a sandwich or not?”‘

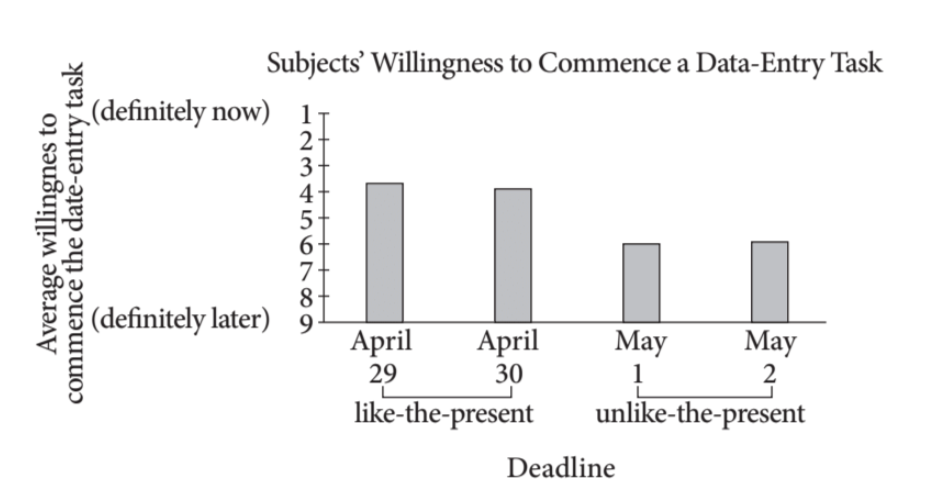

Ms. Tu and Dr. Soman advise in their paper that “the key step in getting things done is to get startee But what drives that? They believe the key that unlocks the implemental mode lies in how people categorise time. They suggest that tasks are more likely to be viewed with an implemental mindset if an imposed deadline is cognitively linked to “now”— a so-called like- the- present scenario. That might be a future date within the same month or calendar year, or pegged to an event with a familiar spot in the mind’s timeline (being given a task at Christmas, say, with a deadline of Easter). Conversely, they suggest, a deadline placed outside such mental constructs (being “unlike-the-present”) exists merely as a circle on a calendar, and as such is more likely to be considered deliberatively and then ignored until the last minute.

To flesh out this idea, the pair carried out five sets of tests, with volunteers ranging from farmers in India to undergraduate students in Toronto. In one test, the farmers were offered a financial incentive to open a bank account and make a deposit within six months. The researchers predicted those approached in June would consider a deadline before December 31st as like-the-present. Those approached in July, by contrast, received a deadline into the next year, and were expected to think of their deadline as unlike-the-present. The distinction worked. Those with a deadline in the same year were nearly four times more likely to open the account immediately as those for whom the deadline lay in the following year. Arbitrary though calendars may be in dividing up time’s continuous flow, they influence the way humans think about time.

The effect can manifest itself in even subtler ways. In another set of experiments, undergraduate students were given a calendar on a Wednesday and were asked to suggest an appropriate day to carry out certain tasks before the following Sunday. The trick was that some were given a calendar with all of the weekdays coloured purple, with weekends in beige (making a visual distinction between a Wednesday and the following Sunday). Others were given a calendar in which every other week, Monday to Sunday, was a solid colour (meaning that a Wednesday and the following Sunday were thus in the same week, and in the same colour). Even this minor visual cue affected how like- or unlike-the-present the respondents tended to view task priorities.

These and other bits of framing and trickery in the research support the same thesis: that making people link a future event to today triggers an implemental response, regardless of how far in the future the deadline actually lies.

Passage 5

This passage is adapted from Eric Hand, “Ancient Magma Plumbing Found Buried below Moon’s Largest Dark Spot” )2014 by American Assocition for the Advancement of Science.

Scientists have found a nearly square peg underneath a round hole—on the Moon. Several kilometers below Oceanus Procellarum, the largest dark spot on the Moon’s near side, scientists have discovered a giant rectangle thought to be the remnants of a geological plumbing system that spilled lava across the Moon about 3.5 billion years ago. The features are similar to rift valleys on Earth—regions where the crust is cooling, contracting, and ripping apart. Their existence shows that the Moon, early in its history, experienced tectonic and volcanic activity normally associated with much bigger planets.

“We’re realizing that the early Moon was a much more dynamic place than we thought; says Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna, a planetary scientist at the Colorado School of Mines in Golden and lead author of a new study of the Procellarum’s geology. The discovery also casts doubt on the decades-old theory that the circular Procellarum region is a basin, or giant crater, created when a large asteroid slammed into the Moon. “We don’t expect a basin rim to have corners; Andrews-Hanna says.

The work is based on data gathered by GRAIL (Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory), a pair of NASA spacecraft that orbited the Moon in 2012. Sensitive to tiny variations in the gravitational tug of the Moon, GRAIL mapped density variations below the surface (because regions of higher density produces slightly higher gravitational forces). Below known impact basins, GRAIL found the expected ringlike patterns, but underneath the Procellarum region, the mysterious rectangle emerged. “It was a striking pattern that demanded an explanation; Andrews-Hanna says.

Scientists already know that the Procellarum region is rich in radioactive elements that billions of years ago would have produced excess heat. The study team theorizes that as this region cooled, the rock would have cracked in geometrical patterns, like honeycomb patterns seen on Earth in basalt formations, but on a much larger scale. The researchers propose that these cracks eventually grew into rift valleys, where magma from the Moon’s mantle welled up and pushed apart blocks of crust. Lava spilled out and paved over the Oceanus Procellarum, creating the dark spot that is seen today. The extra weight of this dense material would have caused the whole region to sink slightly and form the topographic low that has made the Procellarum seem like a basin.

With the discovery, the Moon joins Earth, Mars, and Venus as Solar system bodies with mapped examples of rifting. There are also similar features near the south pole of Enceladus, the moon of Saturn that is spewing water into space from cracks in an ice shell.

Andrews-Hanna and colleagues have made a good case, says Herbert Frey, a planetary scientist at NASNs Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, even though the newly described features are surprising. The Moon is not big enough to have the same strong convective cooling process that Earth has in its interior, he explains, and ordinarily convection is one of the main mechanisms thought to lead to large-scale rifting. So just what caused the rifting remains unclear. “It just means the Moon continues to surprise us,” he says. Frey adds that a remaining mystery is why the rectangular features were found only beneath Oceanus Procellarum. Even if the rifting is explained by the excess radioactive elements, there is still no definitive explanation for why only the near side of the Moon ended up enriched.

2018年 3月 (亞洲) SAT 考試閱讀題目

Ivy-Way 學生在上課的過程就會做到2018年3月以及其他的官方歷年考題。除此之外,我們也有讓學生來我們的教室或在家做模考的服務讓學生評估自己的學習進度並看到成績。如果你想預約時間來我們的教室或在家做模考,請聯繫我們!

Also in:

![]() 简中 (简中)

简中 (简中)